Mirliton How-To Tips

Search tips by keyword:

Managing Vine Borers in Mirlitons (chayote)

I have researched how to manage squash vine borers and there is remarkably little scientific research that will help the home gardener. Big commercial growers use a chemical drench, but that’s no help for organic gardeners. I have heard of wrapping the base of plants with aluminum foil. Maybe that works, but I have not found any rigorously controlled studies of the methods.

Physical barriers and BT (Bacillus thuringiensis) appear to be the most effective management methods. Barriers such as row covers in the spring will help prevent the moths from laying eggs. Regular foliar spraying of BT (Bacillus thuringiensis) appears to be the most effective way to manage squash vine borers. There is persuasive research that BT works on cucurbits like mirlitons (chayote). Start spraying the vines early in the spring and continue throughout the season (don’t mix with oils because they can kill the vine in hot weather).

Some people inject the BT into the vine with syringes, but this will not work because larvae don’t consume BT and it will only kill the larvae if it reaches their gut.

Click here for a short overview of vine borers and how to manage them.

Click here for the best article I found on BT for managing vine borers.

Click here to read about how it is safe for humans to use on crops.

How to Identify and Control Leaffooted Stink Bugs on Mirlitons (chayote)

Leaffooted stink bugs have invaded our mirliton gardens and orchards. They feed on flowers and fruit, killing flowers and injecting enzymes and diseases into the fruits that ruin the flavors or bruise them. And, yes, they stink.

There are several leaffooted stink bug species in the Gulf Coast South, but the principal culprit is a new arrival Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas), widely known as the “western leaffooted bug”. They are with us year-round and overwinter in weeds and tree bark. They emerge in the spring as “nymphs” (immature bugs) and go through five stages called instars. We will concentrate on two of the stages that gardeners are most likely to see on their vines: nymphs and mature bugs.

How to Identify:

Identifying leaffooted bugs is tricky since they look almost identical to assassin bugs, which are beneficial insects that eat bad bugs and don’t damage plants. Because they are physically similar, sometimes people try to distinguish them based on the different markings of the two species. That will work for mature stink bugs, but markings are not always useful for nymphs because they don’t appear in all instars. For example, the characteristic leaf-like “flared” back legs don’t appear in all stages of a leaffooted bug’s life (see the two photos below of nymphs with no flared legs on a mirliton fruit and flowers). A simpler and more reliable way to identify stink bugs is by behavior:

Nymph stage: For most of the growing season, stink bug nymphs are easily identified by their aggregating (swarming) behavior. They like to aggregate into small gangs and search for young flowers and immature fruit. In contrast, assassin bugs are solitary hunters, even as nymphs, and won’t be found in gangs. So don’t t worry about markings; if they behave like a gang, then they are stink bugs. You can control them at this early stage with regular spraying throughout the growing season with insecticidal soap or organic pesticides such as Bee Safe Organicide that won’t harm bees.

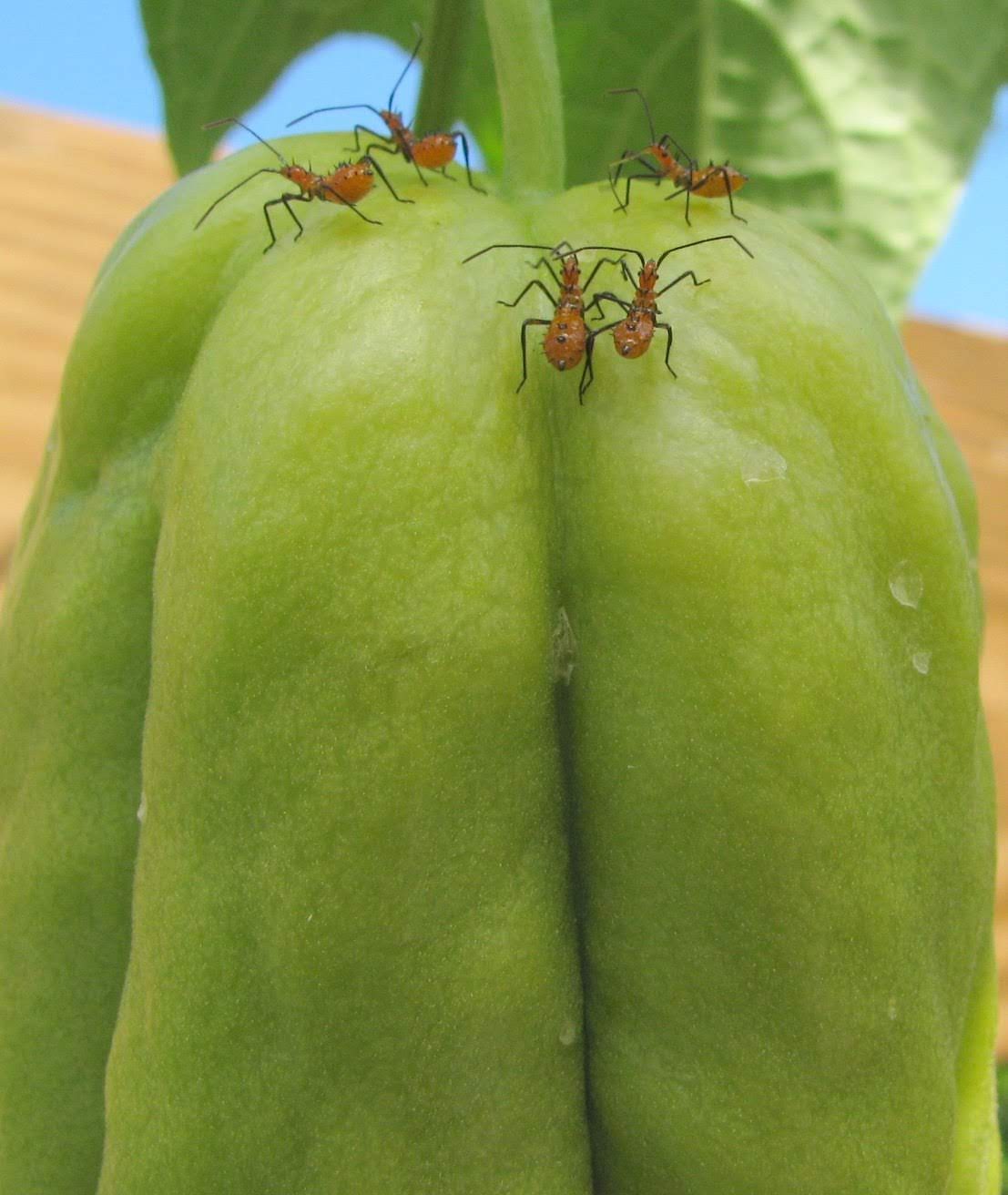

Immature nymph leaffooted bugs in characteristic swarming behavior. Note that at this stage, they don’t have the flared back legs.

Stink bug nymph feeding on immature flowers (also, no flared back legs)

Stink bug damage to young mirliton fruit. Note exudate emerging on top right in a bubble.

Mature stage. Adults can’t be sprayed away; they have a hard exoskeletal structure that protects them from topical insecticides. They are also solitary foragers like assassin bugs, but they are easily identified because they are vegetarians. In contrast, assassin bugs only eat other bugs while leaffooted bugs feed on flowers and fruits. They have to be removed by hand by picking them off by hand, sucking them up with a portable vacuum, or catching them with a butterfly net.

I prefer the hand vacuum (with a homemade 1/2 inch diameter PVC extension—see below) because stink bugs are highly aware and will instantly dash away at the sight of a large extension. Plus, you are less likely to damage flowers. The contents of the vacuum can be emptied into a pail of water with insecticide. Leaffooted bugs and assassin bugs are quick and elusive and difficult to identify as adults. If you accidentally removed an assassin bug, it will not hurt the species since they forage everywhere, unlike leaffooted bugs that target your vegetables and fruits.

Mature leaffooted bug. Note white mark across the back and the well-developed flared “leaves” on the back legs.

Monitor For Stinkbugs Daily:

The key to managing pests is knowing which ones are on your vine because early intervention is critical. Closely scout your vine every day, top and bottoms of leaves, and use sticky yellow insect traps to collect specimens. Click here for sticky traps.

Click here for an excellent recently updated fact sheet on Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas)

The Dewalt 20v. portable vacuum has the power to vacuum up large bugs and can be used for household and automotive cleaning. An accessory kit is available and that will allow you to fit it with a 1/2-inch PVC pipe extension.

Identifying and Contolling Powdery Mildew in Mirlitons

Powdery Mildew on a leaf in the early stages of the infection. The best time to diagnose powdery mildew is in the early stage on mostly green leaves. It starts as irregular pale yellow blotches that combine until the whole leaf is yellow.

Powdery mildew is a troublesome plant disease, but thankfully, it is never lethal. It’s largely a Spring disease because it thrives in cool, damp weather, so it’s the first disease you will see in the mirliton growth cycle. The good news is that there’s an effective organic fungicide that manages the disease.

The signs of powdery mildew on mirlitons are not the same as on most other plants. Gardeners are often advised to look for a white powder on the leaf surface. But that seldom appears on mirliton leaves–probably because the spring rains wash off the leaves. The most obvious signs will be yellowing, dead leaves, and by that time, the infection will have advanced. And yellowing leaves can also be caused by overwatering.

So, what’s the best way to spot the disease? The most accurate way to identify powdery mildew in its early stages is to examine the seemingly healthy green leaves near yellowing ones. The early signs of mildew are irregular, faded yellow blotches like those in the photo above. That is the fungus forming little colonies that will eventually turn into bright yellow leaves.

If you find signs of the disease, there is a highly effective organic fungicide that can control it: potassium bicarbonate. It can completely eradicate the disease in three weeks and works on downy mildew as well.

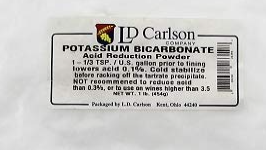

We recommend L.D. Carlson’s potassium bicarbonate because the manufacturer has verified with a Certificate of Authority (COA) that it is at least 99.5% pure. It’s generally sold in one-pound quantities, which is more than you will need, but it has a long shelf life, and you can share it with other growers. Click here to order online.

L.D. Carlson’s potassium bicarbonate.

If you are using a 99.5% pure potassium bicarbonate product, mix one tablespoon with a gallon of water and shake vigorously. Then spray only in the evening and thoroughly wet the tops and bottoms of all leaves. Apply once a week for three weeks until there are no signs of early infection (faded yellow blotches on green leaves).

For a more thorough article on powdery mildew and mirlitons, see my paper here.

Making Spring Mirlitons Sprout

Sprouting mirliton.

We occasionally get a Spring mirliton crop and decide to gift or sell them to others to grow. You could plant them in small containers and sell them that way, but that would mean that potential growers would have to transplant them into the ground during the full heat of the summer. That would be risky. That’s why we recommend that growers sell their fruit as sprouts as soon as possible after picking them. Sprouts can be safely planted in May-June with a simple shade technique (click here). So how do you expedite sprouting?

Mirlitons sprout (germinate) in response to warm weather. Joseph Boudreaux taught me the simple technique for incubating mirlitons in May: Place them in a warm place outside and they’ll sprout within 10-14 days. It’s best to place them away from the direct sun and inside a container such as a milk crate where varmints can’t get them (squirrels, possums, and rats). As soon as they begin to sprout, you can assure people that they are viable seeds and ready to plant.

How To Read Mirliton Leaves for Vine Watering Needs

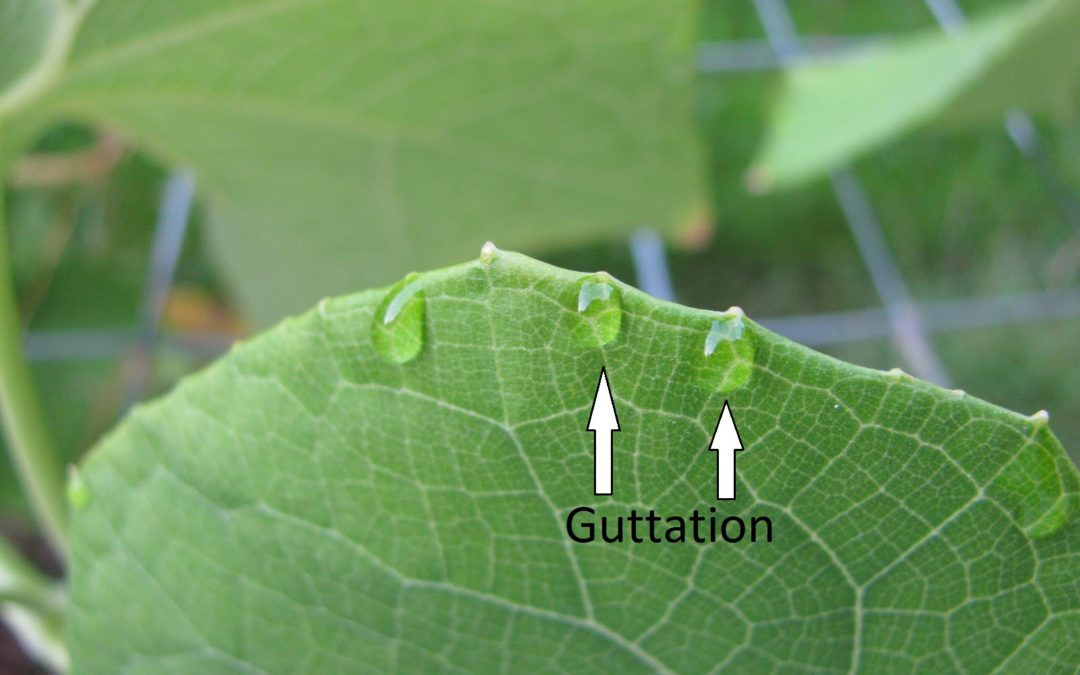

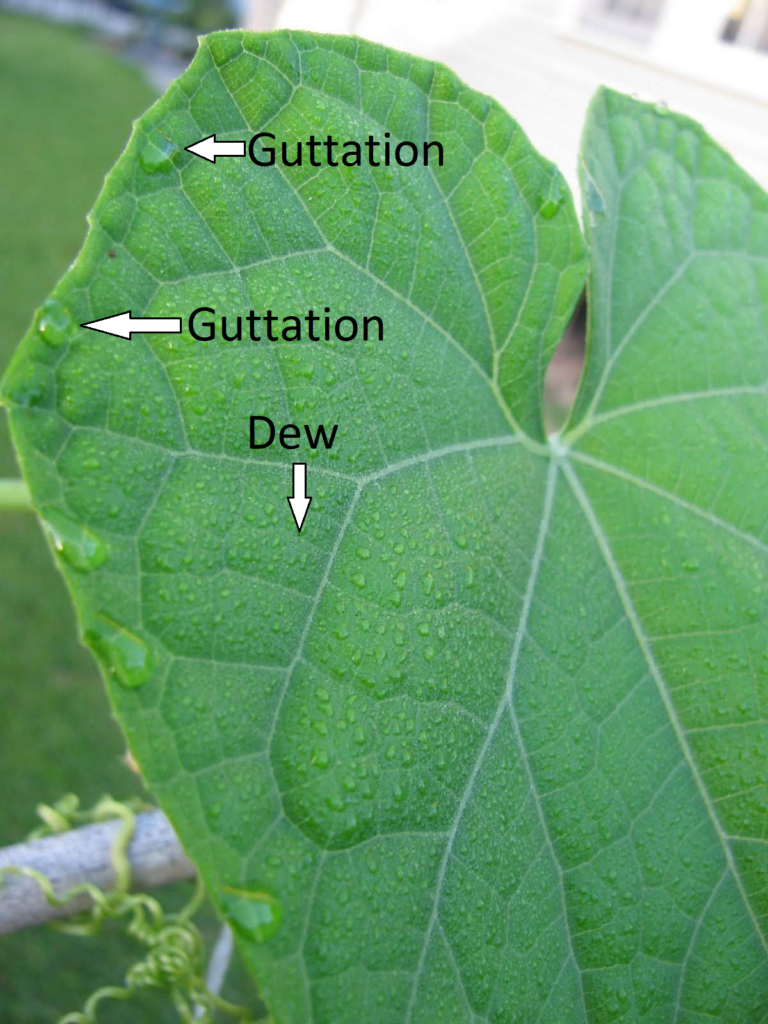

Guttation forming on leaf tips and edges

Your mirliton will tell you every morning how much water its roots are accessing. It is called “guttation.” If there is more than adequate soil moisture available at night, mirlitons will send the excess to the leaves where it will be visible in large droplets on the margins of the leaves. The water exudes from glands at the tip of the leaves. Guttation means the plant has more than enough water; if you don’t see guttation for several days, then it’s probably time to water. Click here for a link to instructional photos of guttation and how to read it (click on each photo for explanations).

Watering Mirlitons

Watering Mirlitons

I could have titled this “How To Water Your Mirliton” but that would be like asking, “How To Care for a Child.” There’s no single answer because each child is different and has different needs at different times in their life. Plants are the same. So this is a set of guidelines instead of rules for watering mirlitons during their three distinct stages in their life cycle.

It used to be said that mirlitons “take care of themselves” and need little care; the increase in hurricanes, floods, and intensive rain days means that is no longer true. Now they need intensive care. No watering technique can remedy a flawed plant site. Mirlitons need quickly draining, well-aerated soil. That means you may have to install drainage (ditches, French drains) in your ground planting; in raised beds, you need lateral exit routes for excess rain, such as side holes or subsurface corrugated pipe. Rapid and wide fluctuations in soil moisture content in your raised bed can stunt growth and hinder flowering and fruiting. These guidelines will generally apply to both planting methods.

Steps to take Before You ever Turn on the Hose:

Get a rain gauge. Place it next to your vine and check it daily. The weather person has no idea how much it rained in your yard—you need to know it for your vine’s health.

Don’t guess about the vine’s water needs. The soil and the leaves will tell you exactly what you need to know if you scout them daily. Learn to read the bamboo stake or soil sampler and the mirliton leaves. They will tell if the vine needs water, and too much water can create a sick vine.

Use a Bamboo Stake or Steel Soil Sampler to gauge soil Moisture: Learn how to use a ½-inch bamboo tomato stake to test soil moisture in the root zone. It will tell you instantly if your vine has too much or too little available moisture. There’s a link at the end of this article to how to read the stake. Or buy a stainless steel soil sampler that allows you see and feel moisture levels beneath the surface (link below)

Check Guttation Daily: Mirlitons will tell you every day if they are quenched or thirsty. Guttation is the droplets of water that form on mirliton leaf edges early in the morning. The presence of guttation means the vine has more than enough available water in the root zone. Three days without guttation mean it probably needs watering. Check the vine first thing in the morning for guttation. Learn to read your mirliton leaves at the link below.

Wilting Does not Mean Water the Vine. A daily wilt in hot weather is normal and healthy mirliton. It’s called “leaf flagging” and it reduces exposure to direct sunlight and toughens the leaves against plant diseases. Watering mirlitons as a reaction to temporary wilt can actually harm the plant. When you see a daytime wilt, wait until the evening and probably see that it recovers.

Never give your vine a shower. That’s a surefire way to start an anthracnose epidemic. The anthracnose pathogens are primarily carried primarily by water through splash-up from the soil or splashed from leaf to leaf. Water gently at ground level with a hose on low, or use drip irrigation.

The Three Stages in the Mirlton Life Cycle:

1. Toddler:

Be careful with the baby. The first impulse when we see a young plant droop is to water our way out of the problem. Don’t do it At the toddler stage, mirlitons are most sensitive to soil moisture issues because their young roots are just emerging. Overwatering is the leading cause of premature death in mirlitons. Prepare for your toddler by installing gentle drip irrigation or an olla. Use the stake and read the leaves daily.

2. Sprawler:

Once the vine is established, it will begin to climb and sprawl. A larger canopy means they need more water. Daily summer showers should provide enough water, but don’t guess–use the stake and read the leaves.

3. Fruiter

The fall is fruiting season and water needs may increase, but use the stake and read the leaves.

Final Thoughts

Watering is not something you simply do to a mirliton vine; it’s something you do with it. It’s a partnership in which both parties have something to say. Listen to your vine.

Bamboo stake instructions here.

Steel Soil Sampler here.

Read the Mirliton Leaves here.

A Master Class in Mirlitons

Ervin Crawford And his Mirliton Vine

In 2008, I was searching for a Louisiana heirloom mirliton to replace the variety I had grown since 1983. The hurricane Katrina flood had killed almost every mirliton in New Orleans. The usual suspects had given me all the normal bad advice: “Buy one at the grocery store. A mirliton is a mirliton. They’ll grow fine.” Nope. I planted, they died; I planted, they died. Over and over.

After a little research, I discovered there were scores of varieties—perhaps hundreds—each adapted to the particular climate and altitude. I had to find the one traditionally grown in Louisiana. I discovered that the Louisiana Department of Agriculture’s monthly Market Bulletin was digitally archived years back. I went through it looking under “fruits and vegetables for sale” and saw one name repeatedly; Ervin Crawford, Pumpkin Center. It was a long shot because the advertisements were decades old, but I called the number. Ervin Crawford answered.

I immediately drove to Pumpkin Center and met him. On that first visit, Ervin gave me about 20 mirlitons and with those 20 plants, I started Mirliton.Org. Ervin played a crucial role in saving the Louisiana heirloom mirliton.

Visiting Ervin’s farm is a pilgrimage everyone should make. He’s a retired airline mechanic and knows more about mirlitons than anyone I know. He has been growing them for five decades, first in Peal River where he was raised, and later in Pumpkin Center where he bought his 20-acre retirement farm. He grows everything; pecans, figs, beans, berries, bees, chickens.

He has a quality found in most successful gardeners–a healthy curiosity. He wanted to know why he had success as well as failures. And failure and mirlitons often go together in the poor sandy pinewoods soil of the area called the Florida Parishes. I have heard people in the region say, “They won’t grow up here.” At first, I thought that they were using the wrong variety, or planting them incorrectly. Ervin taught that the problem was not the soil, it was what was beneath the soil.

Soil sample tests tell you a great deal, but they won’t tell you what you need to successfully grow mirlitons. Mirlitons are shallow-root plants and they sink or swim depending on subsurface drainage. If the soil doesn’t drain quickly enough, the roots can’t absorb oxygen, and the plant founders or dies. Building a raised bed on top of poorly-drained soil may result in a mud boat. The bed has to have an outlet to either absorb or remove excess water. So to succeed, you need to know the geology and history of the land you are gardening on–and Ervin asked the right questions when he first got to Pumpkin Center.

Ervin learned that Pumpkin Center’s soil was considerably different from Pearl River, where he had learned gardening. Pearl River was a loamy basin soil, rich and porous. In contrast, Pumpkin Center was in the middle of the great Piney Flats that stretches from Florida to Texas. It was notoriously bad poor soil—sandy and acidic. When he once had some excavation work done, he saw that solid white clay lay a few feet down–a real barrier to drainage.

I realized that I had never asked those questions about where I was gardening. To grow mirlitons, you have to be part geologist, hydrologist, and historian. You don’t have to become an expert; just enough knowledge to benefit your mirliton.

As I learned more about the history of where I was gardening, I realized that my mirlitons had often thrived in spite of me. I never once had asked what was under that topsoil or what was there 100 years ago.

I do now, thanks to Ervin.

How to Plant Spring Mirliton (chayote) Sprouts in Hot Weather

Spring mirlitons are normally sold unsprouted because they are picked fresh from the vine in early May. The first step before planting is to sprout the mirliton. You can speed the process by incubating it—keeping it as warm as possible. If it is above 80° outside, place the mirliton in a shaded area. Or you can incubate it inside your home by placing it in a small plastic trash can or 5-gallon container with a lamp or small heating pad on low. The ideal temperature is 80°-85°. This will promote rapid sprouting within 10-14 days. (here is how I did it)

As soon as the seed begins to emerge (sticks out its tongue), it needs to be planted—but differently from the fall ones. In May, temperatures can run in the 90s along the Gulf Coast, and I have found that sometimes they won’t send up a shoot in extreme heat. Instead, the shoot spirals under the seed. (Figure 1).

The solution is simple. Plant the sprout as you normally would, but put a temporary shade cover over it —a milk crate with a piece of shade cloth over it or a piece of cardboard on top will work fine. Cover the crate with chicken wire to ward off varmints. Once the shoot emerges, remove the crate and stake up the vine.

Figure 1.

Help! My Mirliton is Wilting!

By Lance Hill

I remember the day I saw my first Mirliton vine wilting. I almost called 911. My first impulse was to water it, which I did, but it did not revive it that day. Miraculously, the next morning, the vine was in perfect shape.

Figure 1: Healthy and Happy Leaves orienting toward the sun and no sign of wilt.

Two Types of Wilt:

There are two types of wilting with mirlitons: temporary and permanent. They are different by degree, but while the temporary wilt can be fixed, the permanent one is a more serious problem. Knowing how to recognize a temporary wilt will help prevent it from getting worse.

Mirlitons are part of the cucurbit family along with cucumbers and melons. Cucurbits that have large, paper-thin leaves lose a great deal of moisture during hot weather—sometimes more quickly than the roots can replenish it. The moisture balance is also complicated by the plants’ shallow root structure. Mirlitons have two ingenious responses to excessive daytime heat: (1) they collapse their leaves so there is less surface exposure to direct sun (stress avoidance), and (2) they wait until the cooler nighttime to uptake more water into the leaves. It’s like humans fighting the heat by wearing a hat and shirt to reduce exposed skin surface and drinking water in the shade to rehydrate.

Temporary Wilt:

You can easily learn to recognize a temporary wilt (also called “leaf flagging”). The leaves will have lost some turgidity but not completely collapsed, as shown in the two photos. When you see this, you can use a soil sampler to sample the soil and see if it is too dry at the roots zone (8″ down). You can also use your hands to feel how firm the leaves and stems (petioles) are. The video at the end of this post demonstrates the proper way to feel for a temporary wilt. The last thing you want to do if the plant is in a temporary wilt is to water the vine when it already has plenty of available soil moisture—you will flood the roots and cause root asphyxia which leads to more wilting. Just wait until the next morning, and if the leaves have fully expanded and properly oriented toward the light, you have no problem. In fact, periodic wilting toughens and leaves and gives them more protection from fungi.

Figure 2: Temporary Wilt. Note that the leaves are no longer oriented toward the sun and are drooping, but not their stems (photo by Kevin De Santiago)

Permanent Wilt:

Permanent wilting is caused by disease, pests, or overwatering that blocks the entire flow of water from the roots to the leaves. If you wait until morning and the leaves are still severely wilted, you have a serious problem. Unfortunately, there is no verified solution to these fungal toxins and insects like vine borers that block the uptake of water. August is the month that anthracnose will most likely attack the mirliton because of heat and frequent rains. There is a link below to how to diagnose anthracnose. But don’t worry: mirlitons can usually withstand a bout with anthracnose and still produce some fruit in the fall. In fact, the vine will acquire increased immunity from anthracnose each time it battles it.

.

Figure 3: Permanent Wilt. Note how even the leaf stems are drooping

Figure 4: Bad news. This is the first sign in leaves of anthracnose. The wedge-shaped pattern of leaf death and the rifle shot hole are clear signs that the disease will soon spread to the stems and block the flow of water.

The reason leaves wilt or hold their shape is because of water pressure. It’s the same reason a limp balloon becomes firm when inflated with air. The key is what scientists call “turgor pressure.” Understanding the simple science of turgor pressure will equip you to identify the difference between temporary and permanent wilting. This short video explains turgor pressure. How to use your hands to test for a temporary wilt. <a href= https://www.mirliton.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Identifying-and-Managing-Anthracnose-in-Mirlitons-FAQ-revdise-2018.pdf

Proper Trellis Material Is Key To Mirliton Growth

Cattle Panel Arch

Proper trellis material is critical for successful mirliton growing. What’s the best material? The short answer is cattle panels. They have the perfect gauge of wire and the ideal mesh size. They come in 4-6 gauge wire diameters and different mesh sizes, but you will want at least 4″ x 4″ so the fruit will hang below the trellis.

Here’s why. For decades, “backyard mirlitons” were grown vertically on the common “chain link” fence with 12 gauge, (1/8 inch) wire. With the advent of the wooden “security fence”, home gardeners lost their built-in trellis. Moreover, research demonstrated that mirlitons fruit more prolifically on horizontal trellises, growers searched for alternative trellising. The problem was that those old chain link fences held a secret: the wire was the perfect diameter for mirliton tendrils. When growers used chicken wire, lathe, bamboo poles, plastic mesh etc. the results were not good. If trellis materials are too large in diameter, the tendrils will not hook and coil and the plant will not grow and extend vigorously; the same is true for materials too small in diameter.

Mirlitons are herbaceous climbers that, in addition to leaves and flowers, have separate tendril structures that branch out in two to five smaller branches. These are slender, string-like coiling climbing organs that are sensitive to contact stimuli. When they come into contact with the correct diameter object, they coil around the object to provide support for the main stem and subsequent fruit. The tendril coils tightly around the anchoring object and coils backward to the plant, creating both an anchor and a spring-like coil. This secures the plant against wind—allowing a little sway—and holds up the stem when fruit begins to weigh it down. Mirliton tendrils are strong but delicate and do not regrow once damaged.

Although the signaling mechanism is not entirely understood, my observation is that when tendrils hook onto a support structure and exert tension on the stem, the meristem (stem tip) is stimulated to grow and extend. A mirliton stem can grow more than 20 feet, and more stem growth means more fruit production. If a stem is grown on a horizontal trellis or arbor with supports that are too large in diameter for the tendril to wrap around, the tendrils will coil unattached in the air, and stem growth will slow if not stop completely. In a sense, the plant only extends to areas that can provide support, and tendrils extending in front of the stem probably exert tension on the main stem, signaling the direction of stem growth and increasing meristem (stem tip) extension. Improper trellis material that does not provide structures for tendrils to hook and coil on can result in stunted plants and stem breakage from wind or fruit weight.

The trick with trellising—and it is a simple trick—is to use trellis support materials that tendrils can easily and readily attach to. That means first providing the vine with support to climb vertically. This is best done using “tomato cages” which are typically constructed of 1/8 inch galvanized wire and then providing string supports to the overhead trellis, using a 3-strand poly twine that is at least 1/8 inch diameter. If you don’t have room for a horizontal trellis, then any wire fencing 4 gauge or thicker will work fine. The mesh size is not important since the fruit will hang on the side of the support structure.

Horizontal trellises need the same minimum wire size. For decades, Louisiana mirliton growers have used overhead trellises with a solid wood framework (4×4 posts and 2×4 rails) covered with “goat fencing” or similar fencing material. Goat fencing is galvanized steel 4” x 4” square pattern fence mesh that is hinge lock woven. The hinge lock makes it easier to work with than welded fence, and the 4″ mesh is large enough for fruit to drop through and hang below the trellis. But you will have to build support for it because it’s not as rigid as welded cattle panel.

The key is that the wire is at least 4 gauge, (1/5 inch). Tendrils do not hook and anchor well on string or wire with diameters less than 1/8 inch. I recently saw a string trellis that used 1/16 inch string and the tendrils refused to hook to it. From an evolutionary perspective, the plant is searching for structures that can support it from wind sway and fruit load; a small twig won’t work and a large branch won’t permit a tight coil. What we have lying around the yard might look like a good trellis idea (PVC pipe, bamboo, old 2x4s), but your mirliton might not agree. This is why cattle panels, with their 4 gauge wire and large mesh, work best. )If you decide to use nylon netting instead, this is the ideal cord diameter and mesh size netting.)

There are many trellis material options other than galvanized fencing. Many growers use heavy concrete reinforcing mesh, which is sold in panels, not rolls, and can often be found in recycling centers. It has a 6”x6” square mesh and is a thicker 9 gauge, which tendrils appear to respond well to. Always be careful to bend in sharp end pieces to avoid accidents (masking tape works remarkably well in blunting end cuts). Also, keep in mind that long stems and plenty of trellis space ensures that leaves are exposed to sun and air circulation which inhibit plant diseases and insect infestations.

Finally, one of the most important steps in trellising is augmenting the vertical path so that new lateral shoots from the bottom of the plant have a pathway to the top since each one of these shoots means more fruit production. It is also important to keep lateral shoots from contacting the ground since soil-borne fungi are transmitted to leaves, and although the ground stems will bear fruit, they are more susceptible to insects. This means that as new lateral shoots emerge, tie thick poly twine to the wire cage at the base and connect it to the overhead trellis at an angle, and pull the string taught. Then gently wrap the new shoot once or twice around the string so tendrils will hook and the shoot has a separate path to the top of your trellis. When a plant begins to grow vigorously, there may be a need to add multiple string paths to spread out the plant at the top and avoid stems from falling over due to their own weight. If you have any question about the appropriateness of a trellis material, simply watch the plant closely and note if the tendrils are hooking and coiling around the material properly. You will find several photographs of properly constructed mirliton trellises on our website’s photo page.