by Lance Hill | Mar 12, 2024 | How To, Mirliton

I used to believe that mirlitons could be grown in full sun. Not anymore. Intensive heat waves in the last few summers destroyed most vines that had been grown in full sun. The only ones that survived were in natural shade or had shade cloths. We learned the hard way that mirlitons need partial shade when there is prolonged heat above 95 degrees. That, along with substantial ground irrigation, can get us through another Heat Dome or intensive heat wave.

Build your trellis so you can easily mount a shade cloth over the vine. You won’t need it unless the temperatures stay above 95°. It can be thrown over the vine or mounted over it. Shade cloths come in different shading percentages, and we recommend 40% cloth with grommets so it does not blow away. They are available at Amazon and most big box stores. Shop around online to find one that will last for years. An Amazon link is here.

by Lance Hill | Feb 28, 2024 | How To, Mirliton

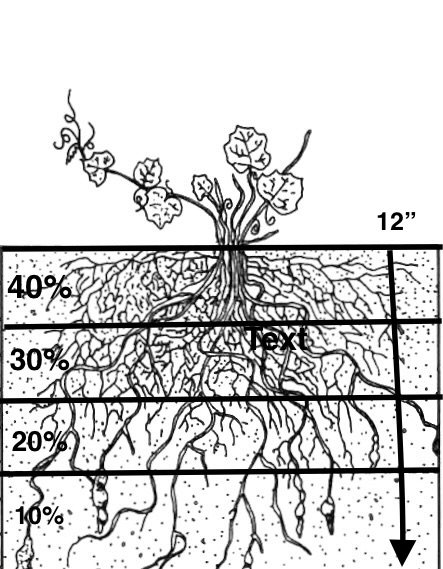

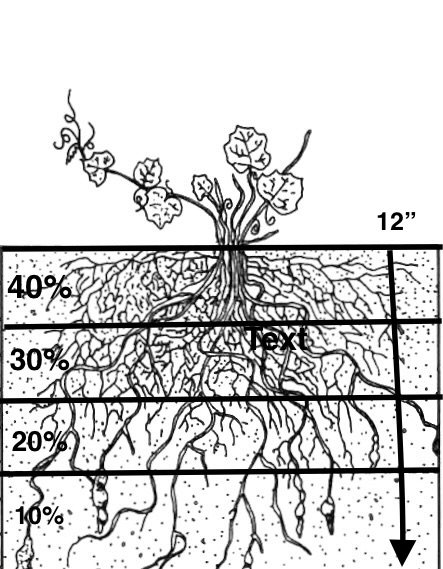

The soil sampler is the simplest way to see how much moisture your mirliton roots are getting. It’s the only quick, inexpensive way to see if you have over-watered or under-watered your vine. The “second knuckle” method of sticking your finger into the soil only tells you what the soil moisture is near the surface; that method does not work with mirlitons because the roots extend downward 8″. Electric meters are also ineffective because they measure electrical conductivity–not soil moisture. The only way to know the available soil moisture beneath your mirliton is to see and touch it, and that’s exactly what a soil sampler allows you to do. Mirliton growers in Brazil have used this method for years. James Leblanc shows you how to take a sample and check the moisture levels at root zone levels.

The soil sampler is the simplest way to see how much moisture your mirliton roots are getting. It’s the only quick, inexpensive way to see if you have over-watered or under-watered your vine. The “second knuckle” method of sticking your finger into the soil only tells you what the soil moisture is near the surface; that method does not work with mirlitons because the roots extend downward 8″. Electric meters are also ineffective because they measure electrical conductivity–not soil moisture. The only way to know the available soil moisture beneath your mirliton is to see and touch it, and that’s exactly what a soil sampler allows you to do. Mirliton growers in Brazil have used this method for years. James Leblanc shows you how to take a sample and check the moisture levels at root zone levels.

See the video here

Buy a soil sampler here.

Mirliton rootzone:

by Lance Hill | Feb 18, 2024 | How To, Mirliton

There are no scientific studies on cross-pollination in mirlliton varieties, so we can’t speak with any certainty about the chances of cross-pollination. Mirlitons are self-pollinating plants and are primarily pollinated by bees. Honey bees are systematic foragers; they will focus on one plant until they have collected all the nectar. That means they are less likely to carry pollen from another plant, thus reducing the risk of cross-pollination.

Because of this, generally, you can grow two different varieties with little risk of cross-pollination. If you grow only one variety at a time, you will have even less risk. But if you want to ensure that the offspring of a plant will be true-to-type, there is a simple way to do that: controlled pollination.

Using controlled pollination will guarantee that the specific fruit you picked from your vine will grow the same variety. Click here to see how to do it.

by Lance Hill | Oct 30, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

Frost Protection

There is a possibility of a damaging frost whenever the temperature drops below 38 degrees. You can protect your mirliton with either a minimum or maximum plan.

Minimum plan: Tent the vine the day before with a tarp or 4mil plastic cover. A FEMA tarp will work well. Weight down the edges of the tarp with bricks (you are trying to trap the heat from the soil inside the enclosure). This will raise the temperature a few degrees and may avert the frost.

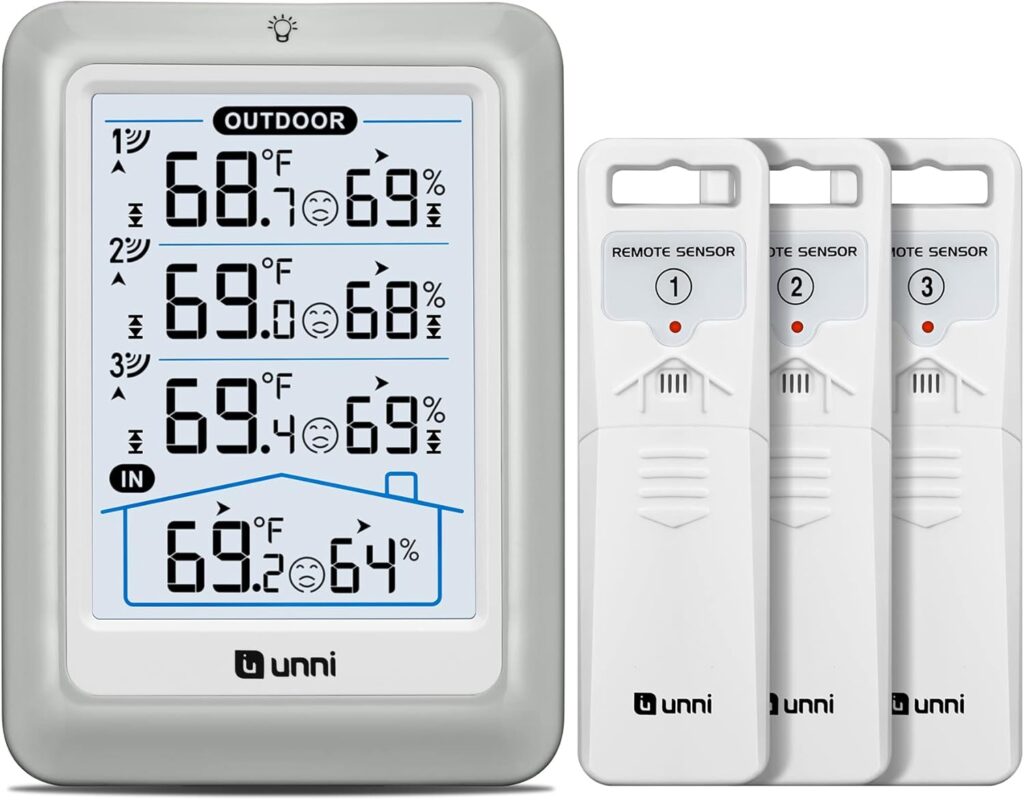

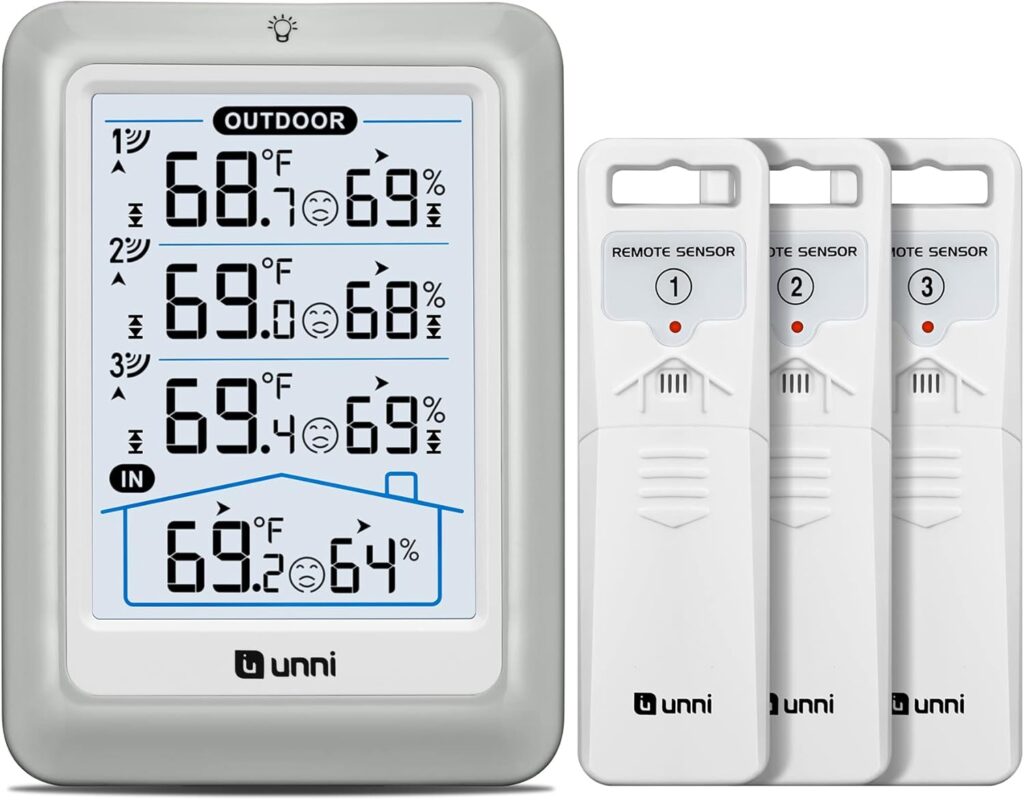

Maximum plan: Add heat to the tent. You will need an extension cord and a small space heater. A space heater will raise the tent’s internal temperature several degrees, which will protect the vine if temperatures dip to 32 degrees. There are also portable gas heaters. Buy a remote thermometer and place the sending unit in the tent enclosure and you will be able to see exactly what the internal temperature is. Remote thermometers will permit you to see what the temperature is in the tented trellis from the comfort of your home. They are the best defense against a freeze–and cost only

$20. Buy it here.

by Lance Hill | Oct 17, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

The Louisiana Mirliton Two-Step

Because of increased extreme weather events like Heat Domes and frequent hurricanes, we need to think entirely differently about when and how to grow mirlitons. We have two chances at a mirliton crop: Spring and Fall. We need to especially take advantage of our cool months, October through May.

Step One

Plant your mirliton seed or container plant in the fall and build a trellis for the vine to grow on all winter. When necessary, temporarily cover it with 4-mil plastic and warm it with a portable heater to protect it on frost/freeze days. By the following spring, the vine will have a large canopy to support flowering–and you will get a spring crop.

Step Two

To help your vine get through the summer, use the same trellis to support a 30% shade cloth to shade the vine from June through August, if necessary. That will give you a a good chance at another crop in the Fall

10’ X 25’ 4-mil plastic sheets

Space Heater

Shade Cloth

Remote Thermometer for Enclosure

by Lance Hill | Apr 30, 2023 | How To, Mirliton

Sometimes bees and other pollinators are not doing their job and you want to ensure that your female flowers are pollinated. The simplest way is to hand pollinate with a slender artist’s brush with dark bristles. The bristles make it clear that you have collected yellow pollen from the males. Using a brush means you do not destroy the males and can return to them for additional pollen. Click on each photo in this link to read the instructions: https://www.mirliton.org/photo/hand-pollinating-of-mirlitons/

The soil sampler is the simplest way to see how much moisture your mirliton roots are getting. It’s the only quick, inexpensive way to see if you have over-watered or under-watered your vine. The “second knuckle” method of sticking your finger into the soil only tells you what the soil moisture is near the surface; that method does not work with mirlitons because the roots extend downward 8″. Electric meters are also ineffective because they measure electrical conductivity–not soil moisture. The only way to know the available soil moisture beneath your mirliton is to see and touch it, and that’s exactly what a soil sampler allows you to do. Mirliton growers in Brazil have used this method for years. James Leblanc shows you how to take a sample and check the moisture levels at root zone levels.

The soil sampler is the simplest way to see how much moisture your mirliton roots are getting. It’s the only quick, inexpensive way to see if you have over-watered or under-watered your vine. The “second knuckle” method of sticking your finger into the soil only tells you what the soil moisture is near the surface; that method does not work with mirlitons because the roots extend downward 8″. Electric meters are also ineffective because they measure electrical conductivity–not soil moisture. The only way to know the available soil moisture beneath your mirliton is to see and touch it, and that’s exactly what a soil sampler allows you to do. Mirliton growers in Brazil have used this method for years. James Leblanc shows you how to take a sample and check the moisture levels at root zone levels.

Recent Comments