by Lance Hill | Oct 14, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

Sprouted Mirliton

You can ground-plant a fall mirliton sprout as late as October, and a spring sprout as late as June. The June planting will have to be initially shaded. See here. Outside these two windows of opportunity, you will have to plant the sprout in a 3-gallon container until you transplant it into the ground. (see below how to container and trellis it). Get the plant growing in a container as soon as possible–it will create a strong root ball for transplanting and it may even produce a spring crop!

1. If your mirliton has not sprouted, (fig. 1) place it horizontally in the warmest room of your house. At 75 degrees, the mirliton should begin to sprout in 2-6 weeks. If it does not spout within two weeks, you can speed up the process by “incubating” the sprout (explained here)

Fig. 1. Unsprouted mirlitons.

2. If your mirliton has already begun to sprout (tongue sticking out) (fig. 2), you are ready to overwinter it to help it develop a root ball.

Fig. 2. Sprout first emerges (above) and shoots extending (below). These are ready to plant.

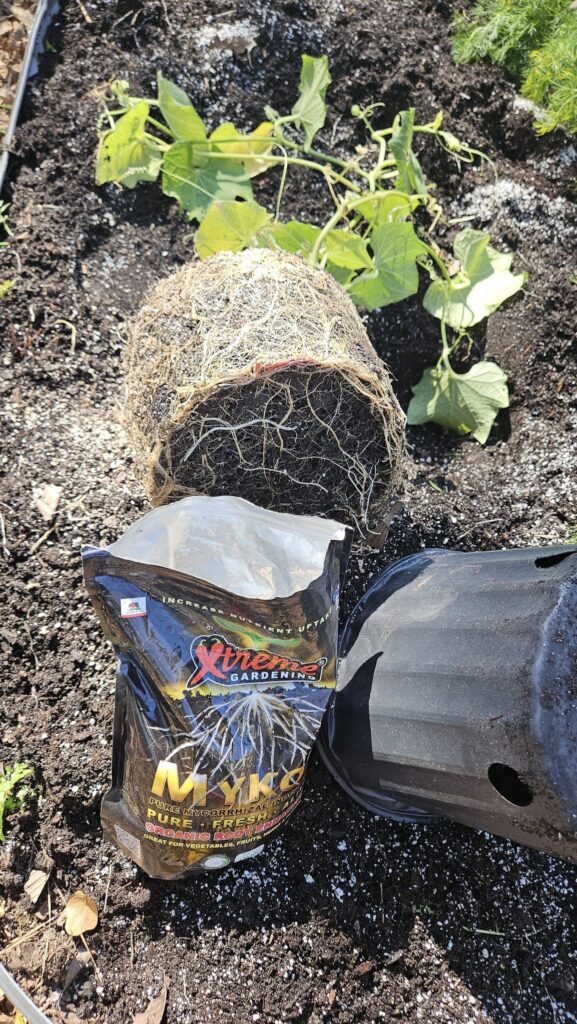

3. Over-wintering: Once your mirliton is sprouted, you plant the whole fruit at a 45-degree angle about 2/3 of the way down with the sprouting end down in a 3-gallon container filled with good potting soil (fig. 3). Water thoroughly the first time. Mirlitons don’t need much water during the overwintering. Here’s how to use a bamboo skewer to test soil moisture. Or you lift the container slightly every few days to gauge if the soil is drying out, and only water if it is noticeably light. David Hubbell has an excellent video on overwintering a mirliton here.

Fig. 3. Sprout planted “sprouting end down” at 45-degree angle with about 2/3 underground in a 3-gallon container.

4. Trellising: Use a 24” – 36″ tomato cage as a trellis. You can prune it back for months to keep it compact, and that won’t hurt the vine. To get it to fill out, you will have to keep it outside in full sun and bring it in when there is the potential for a frost or freeze. The goal is to develop a good root ball. When you transplant it into the ground in the spring, the vine can be unwound from the tomato cage, and the canopy can be attached to your garden trellis (see below images).

Vine trellised on a tomato cage.

Top-down view of vine trellised on a tomato cage.

Vine untangled from the tomato cage is ready to transplant into the ground.

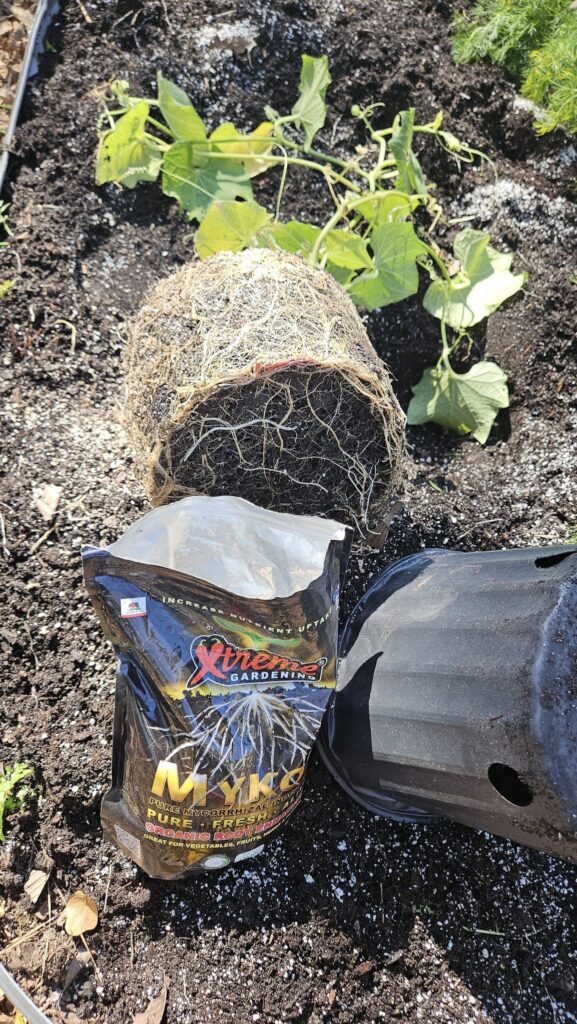

5. Transplanting: When the possibility of a spring frost passes, you can transplant it into the ground. If your container plant is well-developed, you can even get a small spring crop! See Mirliton.Org for instructions on building a grow site and general procedures for watering, fertilization, shading, and plant pests and diseases. Click here for Mirliton.Org to find answers to all your Mirliton growing questions. Join the national mirliton gardeners Facebook Group and post questions and follow the progress of other Mirliton gardeners here.

Well-developed root ball on a 3-gallon plant ready to transplant into the ground.

by Lance Hill | Sep 2, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

Meet The Squirrelator

Well, it doesn’t eliminate them, but it does scare them off, and anyone who has ever grown mirlitons knows that squirrels eat the vine endings and steal the fruit. What to do? A wise old extension agent in Mississippi once said, “If there are 100 cures for something, probably none of them work.” I tried a 100 for squirrels: CDs, noise repellers, and cayenne on the bird seed (the cajun squirrels loved it). None of them worked. This motion-activated sprinkler shoots a short burst of water in an arc over your vine.

David Hubbell tested it for the last two years —complete with a game camera that he used to monitor it. The thing works. It is based on the simple principle: Did you ever see a squirrel dancing in the rain?

They work for other crops and will also keep your neighbors from pilfering your garden at night.

It’s available at most online stores, but here’s the Amazon link.

by Lance Hill | Sep 1, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

Mirliton vine the day after a frost that was protected with a rotary sprinkler. The vine is healthy and ready to produce.

A damaged portion of the same vine that was beyond the reach of the sprinkler.

No one wants to nurse a mirliton for months through droughts, floods, and hurricanes, just to have Jack Frost arrive and kill all your flowers before they can fruit. Sprinklers are the most effective, simplest, and least expensive way to protect mirlitons from an early frost. Moreover, hot weather is the ideal time to set up your sprinkler and adjust it because you don’t want to be running around getting soaked in freezing weather.

Horticulturalists in the South seldom recommend sprinklers because most home gardeners grow soft-tissue vegetables that ripen long beroe the threat of fall frost. But we can find excellent advice from Canadian experts who have perfected the sprinkler systems to protect strawberries from early Sring frosts. We used their experience to design a simple and effective defense against temperatures down to 38 degrees in the fall.

Spraying water on a plant to warm it up seems counter-intuitive, but it works because of a simple principle; when water evaporates from the leaves, it transfers heat into the plant. And when changes to ice on the surface of a plant, it will add heat to that plant. Frankly, the science baffles me, but if you want to know more about it, click here for the Canadian study. For our purposes, the sprinkler frost-defense steps are simple:

Sprinkler Set Up:

1. Place a rotary sprinkler with a metal spike securely on the ground and connect a garden hose to it.

2. Turn the hose on and adjust the sprinkler and mount so that the stream covers the entire vine. Any sprinkler will do, but it’s best to use an impulse sprinkler that can spray a 180-degree arc so you can cover the entire vine. You may have to angle it up.

3. Secure the metal spike so that it does not move when the water is left on for several hours.

When and How to Use the Sprinkler system:

1. Watch the temperature forecast. If the temperature is predicted to go below 38 degrees that night, turn the sprinkler on at sunset and make sure it covers the entire vine.

2. Normally, the coldest part of the night is 4:00-6:00 a.m, so you can turn off the sprinkler after sunrise if the forecast is for temperatures above 40 degrees during the day.

That’s it. We have tested this system on mirlitons for over 10 years and every time it has worked and saved the vines. In 2012, Leo Jones in Harvey, Louisiana used the sprinkler for only part of his vine– it lived while the rest of the vine died (photo above). In 2019, Renee Lapelrolie also used sprinkler heads on only part of her vine, and again, only the protected portion survived (photo below). Not only can the sprinkler protect the vine in the fall, but during a mild winter, it can be used instead to keep the vine alive for a Spring crop.

Buying a sprinkler:

The Rain Bird impulse sprinkler is the best sprinkler head. You can buy it with the reinforced stake and it can cover a vine 40 feet long. There are other brands available, but the Rain Bird is the only one I have had experience with.

Rain Bird Sprinkler Head With Metal Spike Base click here.

How to Adjust Rain Bird click here.

Canadian strawberry frost-protection instruction publication, click here.

Rene Laperolie’s mirliton vine after the 2019 frost. In the foreground, the sprinkler protected the vine. In the background, the unprotected vine was damaged.

by Lance Hill | Aug 10, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

I have researched how to manage squash vine borers and there is remarkably little scientific research that will help the home gardener. Big commercial growers use a chemical drench, but that’s no help for organic gardeners. I have heard of wrapping the base of plants with aluminum foil. Maybe that works, but I have not found any rigorously controlled studies of the methods.

Physical barriers and BT (Bacillus thuringiensis) appear to be the most effective management methods. Barriers such as row covers in the spring will help prevent the moths from laying eggs. Regular foliar spraying of BT (Bacillus thuringiensis) appears to be the most effective way to manage squash vine borers. There is persuasive research that BT works on cucurbits like mirlitons (chayote). Start spraying the vines early in the spring and continue throughout the season (don’t mix with oils because they can kill the vine in hot weather).

Some people inject the BT into the vine with syringes, but this will not work because larvae don’t consume BT and it will only kill the larvae if it reaches their gut.

Click here for a short overview of vine borers and how to manage them.

Click here for the best article I found on BT for managing vine borers.

Click here to read about how it is safe for humans to use on crops.

by Lance Hill | Aug 7, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

Leaffooted stink bugs have invaded our mirliton gardens and orchards. They feed on flowers and fruit, killing flowers and injecting enzymes and diseases into the fruits that ruin the flavors or bruise them. And, yes, they stink.

There are several leaffooted stink bug species in the Gulf Coast South, but the principal culprit is a new arrival Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas), widely known as the “western leaffooted bug”. They are with us year-round and overwinter in weeds and tree bark. They emerge in the spring as “nymphs” (immature bugs) and go through five stages called instars. We will concentrate on two of the stages that gardeners are most likely to see on their vines: nymphs and mature bugs.

How to Identify:

Identifying leaffooted bugs is tricky since they look almost identical to assassin bugs, which are beneficial insects that eat bad bugs and don’t damage plants. Because they are physically similar, sometimes people try to distinguish them based on the different markings of the two species. That will work for mature stink bugs, but markings are not always useful for nymphs because they don’t appear in all instars. For example, the characteristic leaf-like “flared” back legs don’t appear in all stages of a leaffooted bug’s life (see the two photos below of nymphs with no flared legs on a mirliton fruit and flowers). A simpler and more reliable way to identify stink bugs is by behavior:

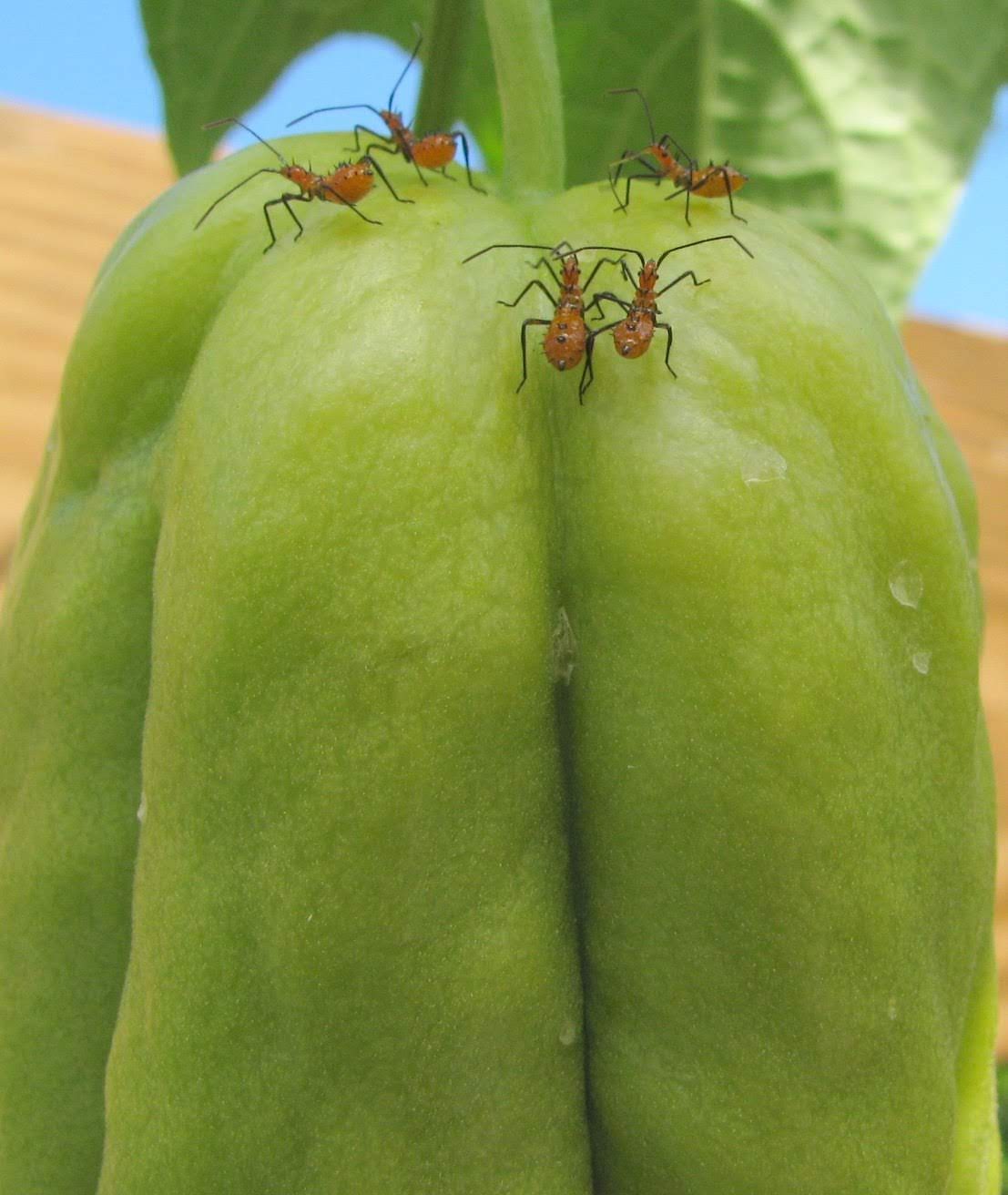

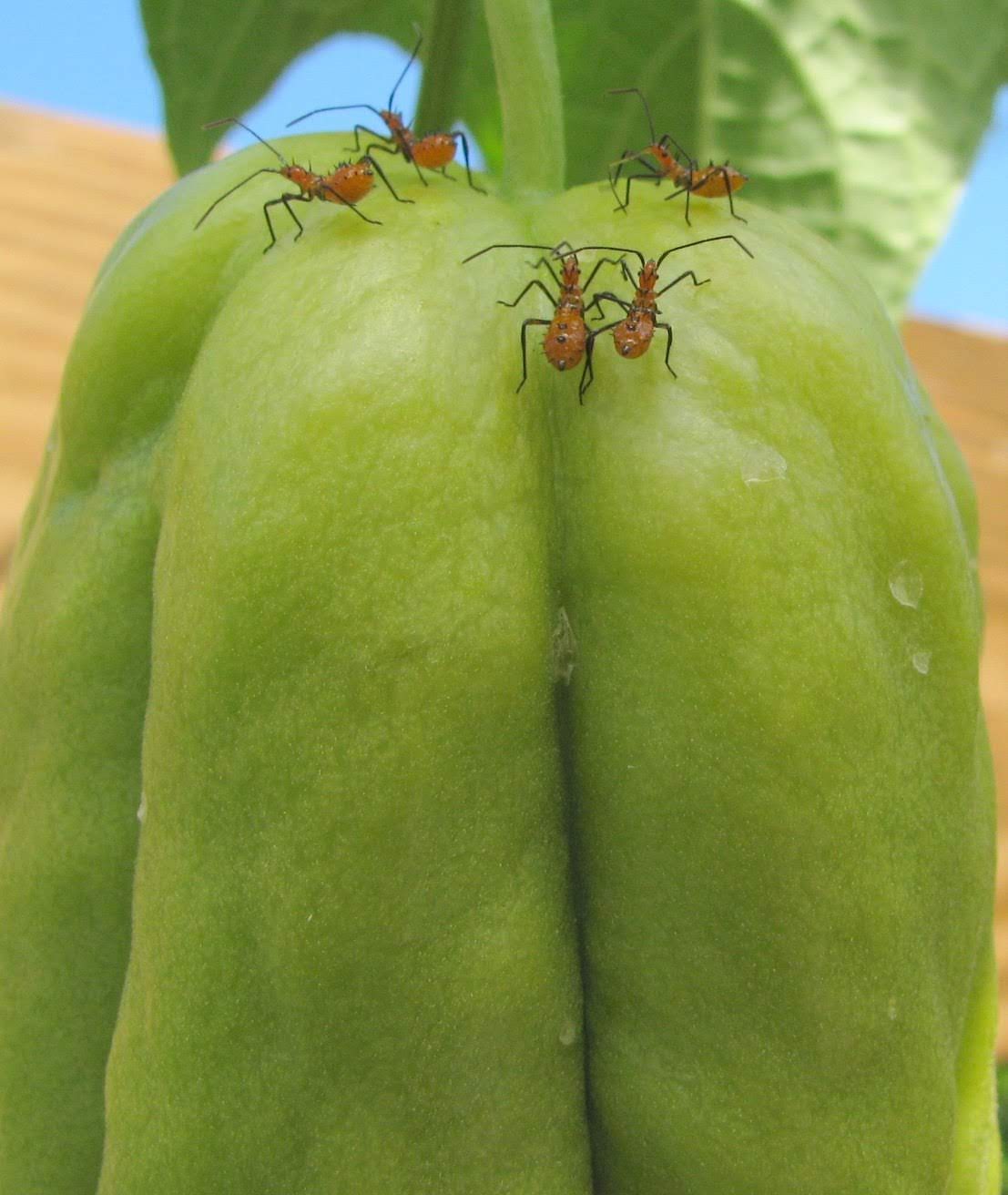

Nymph stage: For most of the growing season, stink bug nymphs are easily identified by their aggregating (swarming) behavior. They like to aggregate into small gangs and search for young flowers and immature fruit. In contrast, assassin bugs are solitary hunters, even as nymphs, and won’t be found in gangs. So don’t t worry about markings; if they behave like a gang, then they are stink bugs. You can control them at this early stage with regular spraying throughout the growing season with insecticidal soap or organic pesticides such as Bee Safe Organicide that won’t harm bees.

Immature nymph leaffooted bugs in characteristic swarming behavior. Note that at this stage, they don’t have the flared back legs.

Stink bug nymph feeding on immature flowers (also, no flared back legs)

Stink bug damage to young mirliton fruit. Note exudate emerging on top right in a bubble.

Mature stage. Adults can’t be sprayed away; they have a hard exoskeletal structure that protects them from topical insecticides. They are also solitary foragers like assassin bugs, but they are easily identified because they are vegetarians. In contrast, assassin bugs only eat other bugs while leaffooted bugs feed on flowers and fruits. They have to be removed by hand by picking them off by hand, sucking them up with a portable vacuum, or catching them with a butterfly net.

I prefer the hand vacuum (with a homemade 1/2 inch diameter PVC extension—see below) because stink bugs are highly aware and will instantly dash away at the sight of a large extension. Plus, you are less likely to damage flowers. The contents of the vacuum can be emptied into a pail of water with insecticide. Leaffooted bugs and assassin bugs are quick and elusive and difficult to identify as adults. If you accidentally removed an assassin bug, it will not hurt the species since they forage everywhere, unlike leaffooted bugs that target your vegetables and fruits.

Mature leaffooted bug. Note white mark across the back and the well-developed flared “leaves” on the back legs.

Monitor For Stinkbugs Daily:

The key to managing pests is knowing which ones are on your vine because early intervention is critical. Closely scout your vine every day, top and bottoms of leaves, and use sticky yellow insect traps to collect specimens. Click here for sticky traps.

Click here for an excellent recently updated fact sheet on Leptoglossus zonatus (Dallas)

The Dewalt 20v. portable vacuum has the power to vacuum up large bugs and can be used for household and automotive cleaning. An accessory kit is available and that will allow you to fit it with a 1/2-inch PVC pipe extension.

by Lance Hill | Jul 17, 2022 | How To, Mirliton

Powdery Mildew on a leaf in the early stages of the infection. The best time to diagnose powdery mildew is in the early stage on mostly green leaves. It starts as irregular pale yellow blotches that combine until the whole leaf is yellow.

Powdery mildew is a troublesome plant disease but, thankfully, never lethal. It’s largely a Spring disease because it thrives in cool, damp weather, so it’s the first disease you will see in the mirliton growth cycle. The good news is that there’s an effective organic fungicide that manages the disease.

The most visible signs of advanced powdery mildew are bright yellow leaves. But chlorotic (yellowing) leaves can be also caused by overwatering or anthracnose. The most accurate way to identify powdery mildew is to examine the seemingly healthy green leaves near yellowing ones. Look for the early signs of mildew are irregular faded yellow blotches like in the photo above. That is the fungus forming little colonies that will eventually into bright yellow leaves.

If you find signs of the disease, there is a highly effective organic fungicide that can control it: potassium bicarbonate. It can completely eradicate the disease in three weeks and works on downy mildew as well.

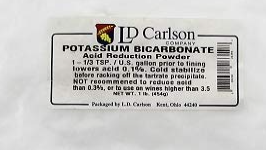

We recommend L.D. Carlson’s potassium bicarbonate because the manufacturer has verified with a Certificate of Authority (COA) that it is at least 99.5% pure. It’s generally sold in one-pound quantities, which is more than you will need, but it has a long shelf life, and you can share it with other growers. Click here to order online.

L.D. Carlson’s potassium bicarbonate.

If you are using a 99.5% pure potassium bicarbonate product, mix one tablespoon with a gallon of water and shake vigorously. Then spray only in the evening and thoroughly wet the tops and bottoms of all leaves. Apply once a week for three weeks until there are no signs of early infection (faded yellow blotches on green leaves).

For a more thorough article on powdery mildew and mirlitons, see my paper here.

Recent Comments