How to Grow True-To-Type Mirliton (chayote) Varieties

You can grow two different varieties of mirliton in the same garden and still ensure that select seeds will produce the same plant as their parent variety. In botany, we call this true-to-type seed—a seed that carries the expected, desired characteristics and qualities of the parent plants. It’s easy to do.

First, the basics of mirliton reproduction. A seed is created through fertilization. Fertilization requires pollination. Pollination is the transfer of pollen from the male part of the flower to the female part of the flower. Remember, pollination happens within the same species level, not between species. A mirliton and a pumpkin cannot cross-pollinate; only varieties of the mirliton species, Sechium edule can interbreed. Mirlitons are monoecious plants because they have both male (staminate flowers) and female (pistillate flowers). The pollen from the male flowers can fertilize the female flowers. This will produce fruit that ensures you will have identical offspring: true-to-type seed.

The problem is that bees, the primary mirliton pollinator, travel several miles foraging flowers and they may introduce pollen from another nearby variety. Some think that if they plant a mirliton fruit, the vine that it makes will produce fruit identical to the planted seed. This is not necessarily true. The confusion arises because plants do not reproduce the same way that humans do. When two humans mate, the immediate offspring is comprised of half the genes of both parents. Mirlitons are different. The characteristics of the fruit on the vine are determined by the genes of the mother plant, regardless of how it was pollinated.

The color, shape, and skin surface of every fruit growing on the vine are created by the genetics of only the mother plant producing the fruit. The father’s genes from the pollen are embedded deep in the inner soft seed that you see when you cut open the mirliton. This inner soft-seed is called the embryo and it contains both the mother’s and father’s genes, but at this stage, the pollen–the father’s genes– don’t affect the fruit characteristics.

The mother plant’s ovary controls the characteristics of the fruit enveloping the embryo, the fruit that we eat which includes the skin type and color. For example, assume that a smooth skin mother plant female flower is cross-pollinated by a spiny-skin male plant flower. The fruit that grows that year will still be a smooth skin fruit. The male pollen does not affect the first generation of fruit. But all the spiny genes are locked into the soft seed in the middle of the fruit, and if you pick that fruit and let it sprout and plant it, the fruit of that plant will have spines if spines is a dominant trait.

So how do you ensure that fruit from your mirliton will be a copy of the mother plant? The answer is simple: use isolation to guarantee a true-to-type seed. If you protect a female flower from pollen from a distant mirliton, you can create a true-to-type seed. You only have to protect a few flowers because you only need the true-to-type seed of the mother variety to grow the next year or to give to another grower. It’s like my dentist used to tell me, “Only floss the teeth you want to keep.”

How to Isolate flowers to Propagate True-To-Type Seed:

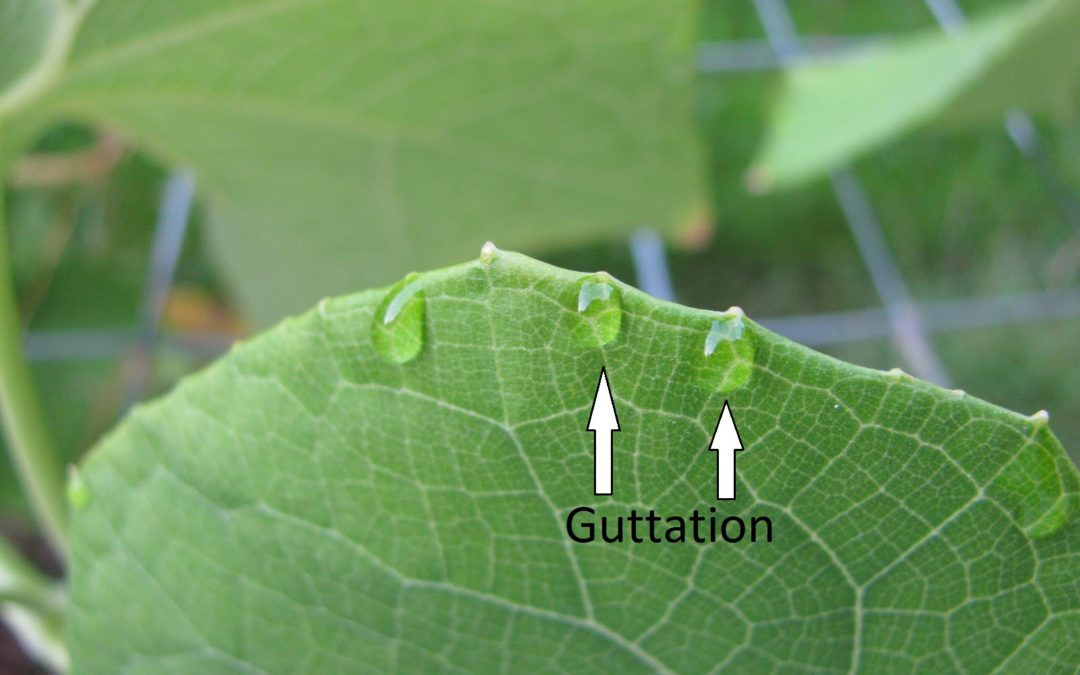

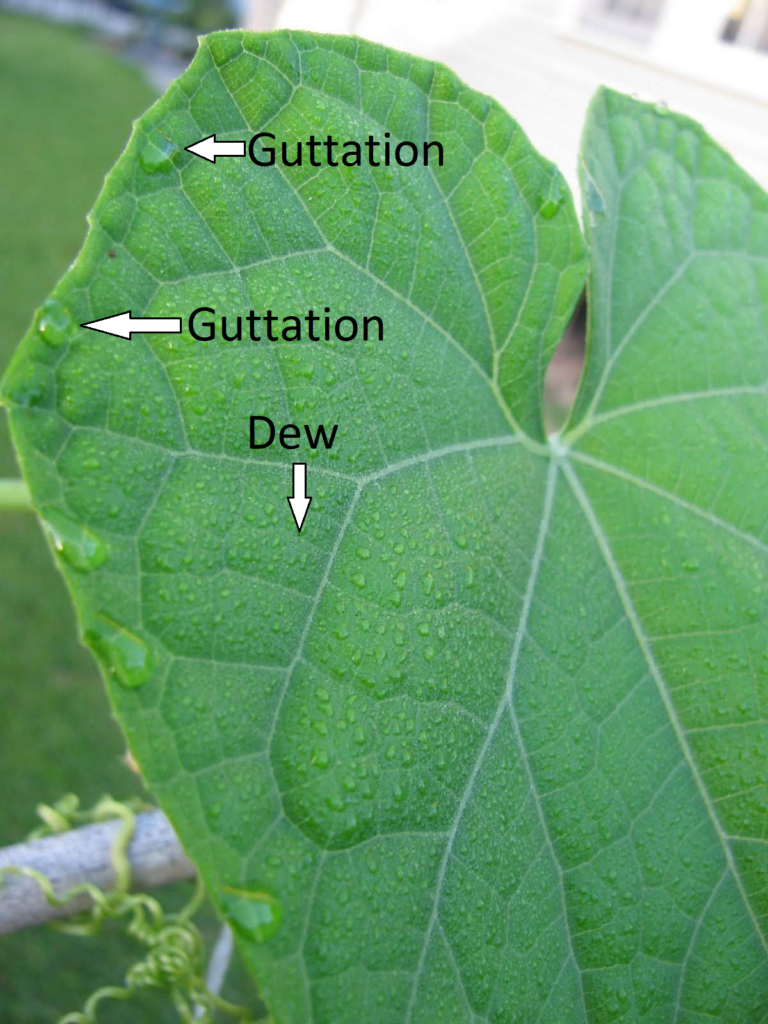

The goal is to ensure that the female flowers on the vine receive only pollen from the male flowers on the same vine. Mirlitons normally first produce an abundance of male flowers in anticipation of the females. Male flowers are easy to recognize; they are little yellow flowers with no appendage (tiny fruit) between the flower and the stem (captioned photos are at the bottom of this article). They tend to grow clusters. After the males appear, watch for female flowers to emerge; they will be far and few between but along the same vine as the males. The female flower petals do not initially open but they have a distinct bulge beneath the flower—a baby mirliton on the peduncle (stalk) between the flower and the vine.

As soon as you identify a female flower and before it begins to open (see attached photos ), enclose it with a small transparent pollination bag to protect it from unwanted pollen. Tie the bag at its base. Then tie a piece of red yarn around the base of the flower to mark it as “control pollinated.” When the female flower is completely open, use an artist’s paintbrush to gather some pollen from the male flowers. You will see the yellow pollen on the brush. Take that pollen to the female flower and dab it onto the pistil and retie the bag.

If the flower is successfully pollinated and fertilized, the petals will fall off the female flowers in three days, leaving the tiny mirliton fruit. You can remove the bag but leave the red yarn as a marker to indicate it is a true-to-type fruit. When mature and sprouted and planted, this seed will produce a plant that is true-to-type.

Materials: Pollination bags: https://www.nativeseeds.org/products/sss006

How to Propagate True-to-Type by Stem Cuttings Mirlitons:

True-to-type mirlitons can also be grown from stem cuttings (vegetative propagation) which will ensure that the plant is a copy of the mother plant. Growing from cuttings is the normal way mirlitons are propagated in Latin America since it (1) ensures uniformity in plant characteristics from generation to generation and (2) cuttings, unlike fruit, are free. Vegetative propagation requires more time and work than controlled pollination, but if you are interested, see the instructions for stem cuttings on the photo page here.

Read the research article on cuttings at: https://www.mirliton.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Mirliton_Vine_Cuttings_Aricle.pd

(Special thanks to Dr. Joe Willis of the LSU AgCenter for his indispensable contributions to this article.)

Male flowers first emerging and opening in clusters.

Unopened female.

Female with opened flower.

Collecting pollen from male.

Brush with pollen on tip.

Dabbing pollen onto female.

Dropped petals on female indicate it was successfully pollinated.

A pollination bag is used to protect female flowers from cross-pollination.

Recent Comments